5q Spinal Muscular Atrophy – Information for Schools

5q Spinal Muscular Atrophy – Information for Schools

This information is for schools where there is already a child who has Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA), and schools where parents are thinking of applying for a place. It aims to give a brief overview of this rare condition.

Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) is a rare, genetic neuromuscular condition. It causes progressive muscle wasting (atrophy) and weakness. The most common form is 5q SMA.

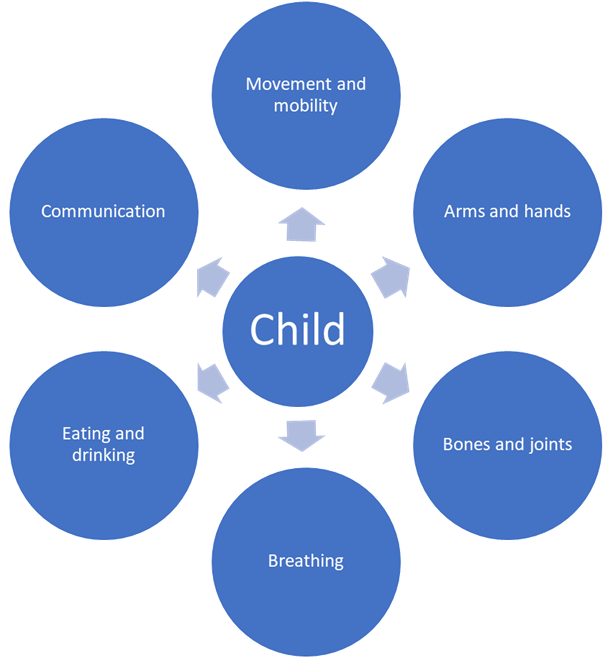

SMA can affect all or only some of the following:

SMA does not usually affect a child’s intelligence or thinking. However, there is increasing awareness that some children with SMA Type 1 (see tab 4) struggle with their general development, learning or understanding. This shows how important it is to spot and address concerns early. Strategies can then be put in place to support individual development and educational attainment..

How SMA impacts on each child varies greatly. The best people to ask about any child at your school are the parent(s) or guardian(s), any supporting professionals and the child themselves. They will also be able to tell you what support and equipment the child needs so that they can be fully included in every learning, social and playing opportunity.

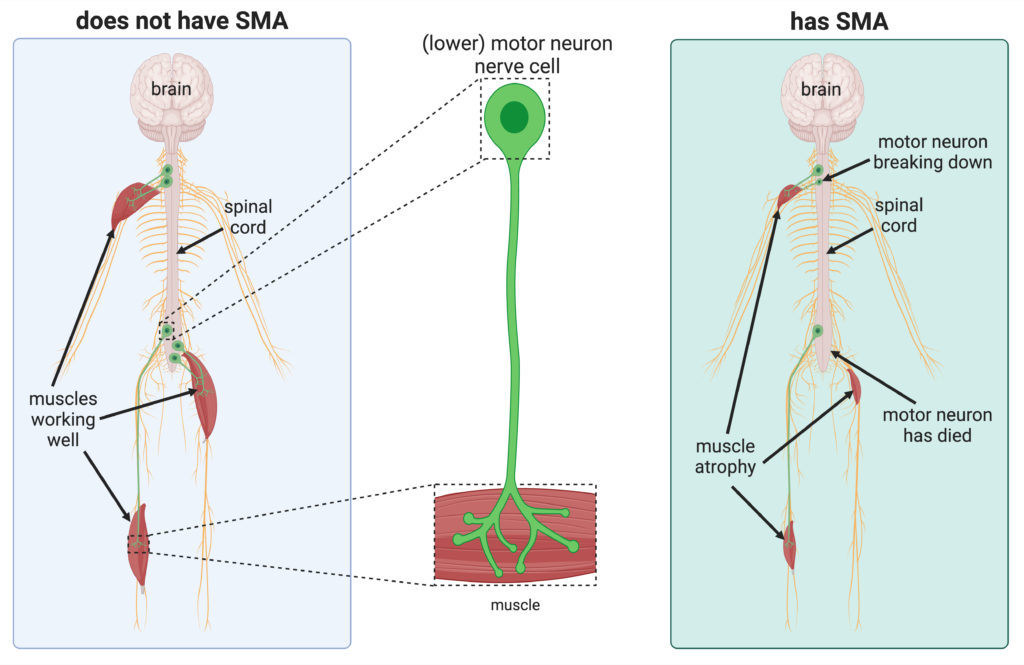

Most people have two genes called the Survival Motor Neuron 1 (SMN1) gene. This produces Survival Motor Neuron (SMN) protein which keeps lower motor neuron nerve cells healthy.

These nerve cells are essential for activating muscles used for crawling and walking, the movement of arms, hands, head and neck, as well as breathing and swallowing.

Most people have two healthy copies of the SMN1 gene. People who have 5q SMA have two ‘altered’ copies of the SMN1 gene. This means they are unable to produce enough SMN protein to have healthy lower motor neurons.

As a result, the lower motor neurons in the spinal cord deteriorate.

Figure adapted from Sleigh et al. (2023). Figure adapted with permission from Reference 1 under the CC BY 4.0 licence

This means that signals are not effectively carried from the brain to the muscles. This makes movement difficult.

The muscles then waste due to a lack of use — this is known as muscular atrophy.

In summary:

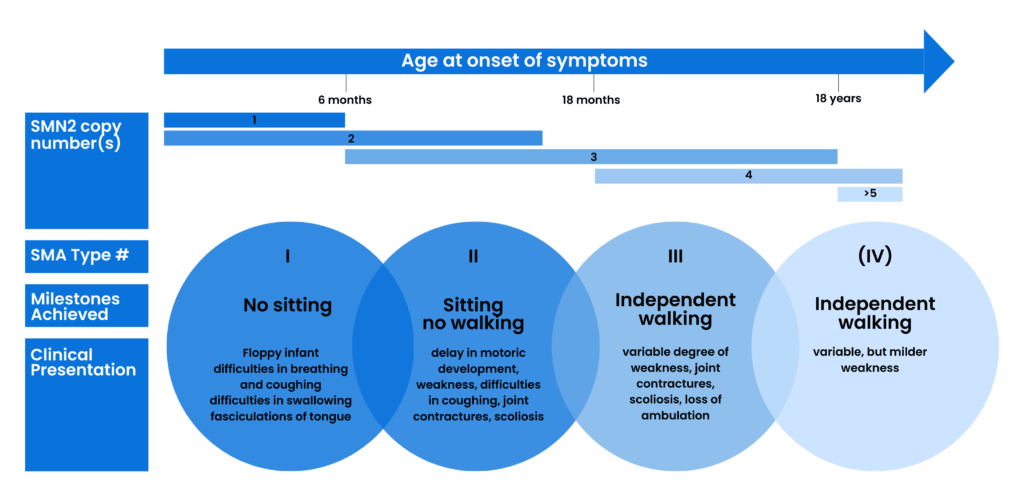

Before drug treatments (also known as ‘disease-modifying’ treatments) became available for 5q SMA, clinicians studied the effects of SMA on people.

This is called the ‘natural history’ of the condition.

This led to 5q SMA being divided into four main types of SMA: Types 1, 2, 3, and 4.

These ‘Types’ of SMA were based on the age that symptoms began, and what physical milestone (e.g. sitting, standing, walking) could be achieved. It was agreed that there could be variation both within and between Types.’

How severe and what impact SMA has varies from person to person, both within and between ‘Types’.

Each child and adult is affected differently.

Clinical classification of SMA subtypes according to onset, milestones achieved, and clinical presentation. Typically associated SMN2 copy numbers are shown. Figure taken with permission from Reference 2 under the CC BY-NC 4.0 licence .

These clinical classifications are still used by doctors for adults, teenagers and children living with SMA. For many, though, care and treatment are changing the outcome of their SMA.

There is no cure for SMA, but since 2016, disease-modifying drug treatments have been gradually introduced. There are now three NHS-funded drug treatments for those who have SMA Type 1, 2 or 3.

These drugs and better care and management of the condition can change what motor milestones (e.g. the ability to sit, stand and walk) babies and children may be able to achieve, and improve their general health.

The treatments work best if started before there is any muscle weakness, or when this is minimal. It is therefore important for treatment to be started as soon as possible.

Children who are already in school will almost all be receiving one of these ongoing treatments:

In July 2021, a ‘one-off’ gene therapy became available in the UK for children who had been diagnosed with SMA Type 1:

Some children who had previously been receiving one of the ongoing treatments stopped this and instead received the gene therapy.

All these treatments continue to work as a child grows and develops. What the outcomes are, or will be, will vary for each individual child. It will depend on factors such as how early treatment was started and how severe the impact of a child’s SMA was at the time. Appropriate, ongoing, individualised health management and care is also critical.

There is lots of further research going on and other drugs are being tested in clinical trials.

-

Every month in the UK, 4 babies are born with 5q SMA.

Recent studies suggest that 5q SMA affects an estimated 1 in 14,000 births. In 2023, this would mean that:

- around 47 babies in the UK were born with 5q SMA.

- approximately 28 of these babies (60%) would have the more severe SMA Type 1.

-

In 2023 there were up to an estimated 1,365 people living with 5q SMA in the UK.

In 2023 there were up to an estimated 1,365 people living with 5q SMA in the UK.

As there is no central source of information, exact numbers are unknown. Worldwide, between 1 and 2 people in every 100,000 have 5q SMA.

-

Although SMA is a rare condition, an estimated 1 in 40 people carry the altered gene. That’s around 1.7 million people in the UK.

Although SMA is a rare condition, an estimated 1 in 40 people carry the altered gene. That’s around 1.7 million people in the UK.

When two ‘carriers’ of the altered gene have a child, for each and every pregnancy there is a one in four chance that the child will have SMA.

See Tabs 11 and 12 on our page Nursery and School >

1. Sleigh J et al. (2023) Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Rare but Treatable Disease of the Nervous System. Frontiers for Young Minds 11:1023423 Under the CC BY 4.0 licence.

2. Schorling D et al. (2019) Advances in Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy – New Phenotypes, New Challenges, New Implications for Care J Neuromuscul Dis 7: 1-13, under the CC BY-NC 4.0 licence.

Version 5

Version 5

Author: SMA UK Information Production Team

Last reviewed: April 2025

Next full review due: November 2025

Links last checked: November 2024

This page, and its links, provide information. This is meant to support, not replace, clinical and professional care.

Find out more about how we produce our information.